Maria Aquaro, who teaches Italian

1. What do you miss most about your home country? And what do you like best in Germany?

Oltre alla mia famiglia, mi mancano il calore della gente, che comunque prima si sentiva molto più di adesso, il mar Jonio e tutti i colori, i sapori e i profumi ad esso collegati.

La cosa che apprezzo di più in Germania è l’aria di libertà che si respira nelle grandi città, il rispetto per il diverso.

2. How has your language/identity changed over time?

La lingua della mia infanzia è l’italiano ma sono sempre stata esposta a più lingue, e sono cresciuta con il desiderio di studiarne tante, per cercare di scoprire, capire, conoscere culture diverse dalla mia. Adesso tante lingue fanno parte della mia lingua interiore.

3. What role does ‘bilingualism’ play in your life?

Io e mio marito abbiamo scelto di vivere in Germania perché abbiamo sempre ritenuto che fosse importante per i nostri figli crescere quantomeno bilingui. Per essere veri cittadini europei è necessario conoscere più lingue europee.

4. What would you recommend someone from your country coming to Germany?

È importante essere consapevoli del fatto che la cultura di appartenenza non è quella “giusta” in assoluto. Per un approccio positivo è necessario fare tabula rasa di tutti i pregiudizi.

5. What was your reaction to Brexit?

Da ragazza ho passato tante estati in Inghilterra a studiare inglese con tanti ragazzi da ogni paese d’Europa. In tutta sincerità sento di essere “diventata europea” proprio in Inghilterra. Ed è per questo che la Brexit è motivo per me di enorme tristezza.

Fredrik Ahnsjoe, who teaches German, and who has also taught Swedish

1.What do you miss most about your home country? And what do you like best in Germany?

Det jag faktiskt saknar mest är somrarna, naturen, kusterna och känslan som infinner sig omedelbart efter att ha passerat gränsen.

2. How has your language/identity changed over time?

Mina föräldrar kom till Tyskland 1973, då var jag två år gammal. Hemma pratades det alltid svenska. Om man sedan bara kommer till Sverige en gång om året några veckor under sommarlovet avbryts språkets naturliga utveckling. Släktingar påpekar då från tid till tid att det låter en aning gammalmodigt när jag pratar…

3. What role does ‘bilingualism’ play in your life?

Att vara tvåspråkig gav mig chansen att få jobba på universitetet här i Augsburg som lektor i svenska – nog det bästa som kan hända en språkmänniska som älskar sitt modersmål men har studerat germanistik i Tyskland. Nu är det Tyska som främmande språk som gäller – inte illa det heller!

4. What would you recommend someone from your country coming to Germany?

Att diskutera är bra, men här lär du dig att ta beslut!

5. What was your reaction to Brexit?

Hur kunde ni?!?

Luis Martín, who teaches Spanish

1. What do you miss most about your home country? And what do you like best in Germany?

Lo que más echo de menos es el mar y el contacto con los míos, mis amigos, el ambiente por las calles, la comida…

De Alemania me gustan los bosques, los veranos en los lagos; también la sensación de que las cosas funcionan…

2. How has your language/identity changed over time?

Sin duda alguna se produce una simbiosis entre las dos lenguas y las dos culturas. Entras en una especie de estado esquizofrénico: no eres de ningún sitio y de los dos a la vez. Vives una sensación de extrañeza y desarraigo constantes: para los de allí soy el alemán, y aquí sigo siendo el español. Digamos que tengo una doble identidad; al fin y al cabo soy géminis… (risas)

3. What role does ‘bilingualism’ play in your life?

El bilingüismo es fundamental en mi vida. Desde que vivo en Alemania es el pan de cada día. Con mis hijos lo integramos desde el primer día. Pero no solo aquí experimento el bilingüismo. También en España vivimos con la familia de Barcelona situaciones de bilinguismo y diglosia.

4. What would you recommend someone from your country coming to Germany?

Que debe tener la mente abierta y aceptar que las cosas aquí son algo diferentes. Ya sabes: In Rome do like the Romans (risas de nuevo)

5. What was your reaction to Brexit?

Incomprensión, tristeza, impotencia frente a la estupidez humana. Creo que ha sido una decisión en la que todos vamos a salir perdiendo. También creo que la población británica ha sido manipulada inflando el sentimiento nacionalista. Fue una lástima que los jóvenes no participaran más activamente en le referéndum; porque serán ellos los que sufrirán las consecuencias en el futuro fuera de la UE.

Christophe Lips, who teaches French

1. What do you miss most about your home country? And what do you like best in Germany?

J’habite à l’étranger depuis si longtemps (quasiment la moitié de ma vie

déjà) que j’ai désormais l’habitude de savoir patienter jusqu’au prochain

séjour pour pouvoir obtenir ce qui pourrait me manquer. En fin de compte, rien

ne me manque plus vraiment, si ce ne sont des petits moments comme lire un

journal/un magazine sur la terrasse d’un petit café dans une petite ville

française 😉

Ce que je préfère en Allemagne : l’aménagement des infrastructures pour

favoriser la mobilité en vélo. Et, au fond, c’est tout un mode de vie (plus

écologique, plus lent, moins stressant) qui est favorisé.

2. How has your language/identity changed over time?

J’ai découvert qu’une identité évolue en fonction des expériences, dont les expériences à l’étranger. J’essaie de m’approprier le “meilleur” (c’est subjectif bien évidemment) de chaque culture que je rencontre pour me construire et avancer dans la direction qui me convient le mieux dans la vie. Mon identité est en constante évolution, au rythme des découvertes d’autres cultures et modes de vie, mais aussi au rythme de mes découvertes linguistiques qui m’aident à comprendre profondément comment une culture est influencée (et influence) un langage.

3. What role does ‘bilingualism’ play in your life?

Je vis dans un environnement trilingue, voire quadrilingue, au quotidien, que ce soit chez moi, ou au travail. C’est un ‘outil’ de travail, de communication, de rencontres et de compréhension de l’Autre et du monde au quotidien.

4. What would you recommend someone from your country coming to Germany?

“Ne traversez pas quand le feu est rouge, sous peine d’essuyer les regards les plus durs!”. Traverser la rue lorsque le feu est rouge en Allemagne (une habitude très répandue en France), c’est, j’ai l’impression, comme si je bousculais l’ordre établi, comme si je ne respectais pas tout un système construit autour du respect des règles qui doit éviter le chaos et favoriser les libertés. Un petit geste anodin pour un Français, mais lourd de conséquences en Allemagne.

5. What was your reaction to Brexit?

Etonné d’abord, parce que je ne pensais pas que cela pouvait arriver. Puis, déçu et triste de voir une Europe qui n’arrive pas/plus à se construire. La construction européenne est certes un processus, avec des progrès et des revers, des hauts et des bas, mais lorsqu’un pays décide de quitter l’Union européenne, le revers n’est pas sans conséquences. Je suis un enfant de l’Union européenne, j’en ai profité à travers mes voyages, les projets financés par l’UE, etc., pour rencontrer l’Autre et continuer de construire (jusque ma propre famille) ce projet humaniste inédit et exceptionnel. Aujourd’hui, elle est fragilisée et cela m’inquiète évidemment. C’est d’autant plus inquiétant que les arguments sont basés sur des questions d’identités et de cultures notamment. Puisqu’il n’est pas possible d’agir directement sur cette décision, tirons-en des leçons! La plus importante à mes yeux : c’est de ne pas/plus faire l’erreur de considérer une identité/une culture comme un phénomène fixe et facilement définissable. L’identité et la culture sont mouvantes, évolutives, dynamiques et bien plus complexes que la simple démarche de poser des étiquettes sans fondements ou de tenter de ‘ranger’ les Autres dans des boîtes. Cette démarche est en effet dangereuse car elle est réductrice et nous empêche de comprendre le monde dans sa riche complexité.

picture: pixabay

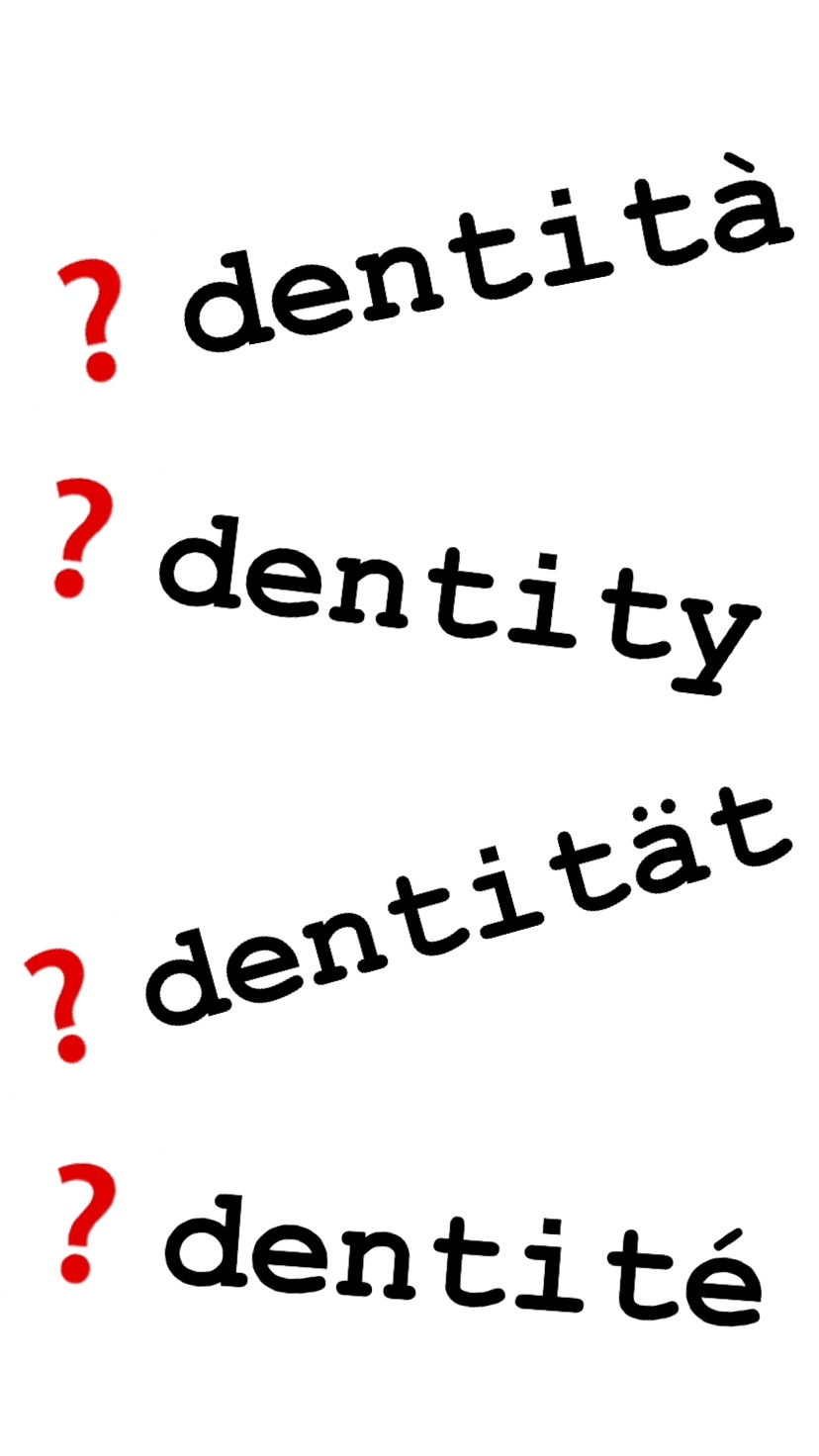

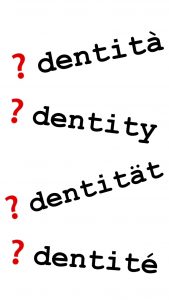

Identità: Il complesso dei dati personali caratteristici e fondamentali che consentono l’individuazione o garantiscono l’autenticità, specialmente dal punto di vista anagrafico o burocratico. Siamo davvero soltanto quello che un libro anagrafico dice di noi?

Identità: Il complesso dei dati personali caratteristici e fondamentali che consentono l’individuazione o garantiscono l’autenticità, specialmente dal punto di vista anagrafico o burocratico. Siamo davvero soltanto quello che un libro anagrafico dice di noi?

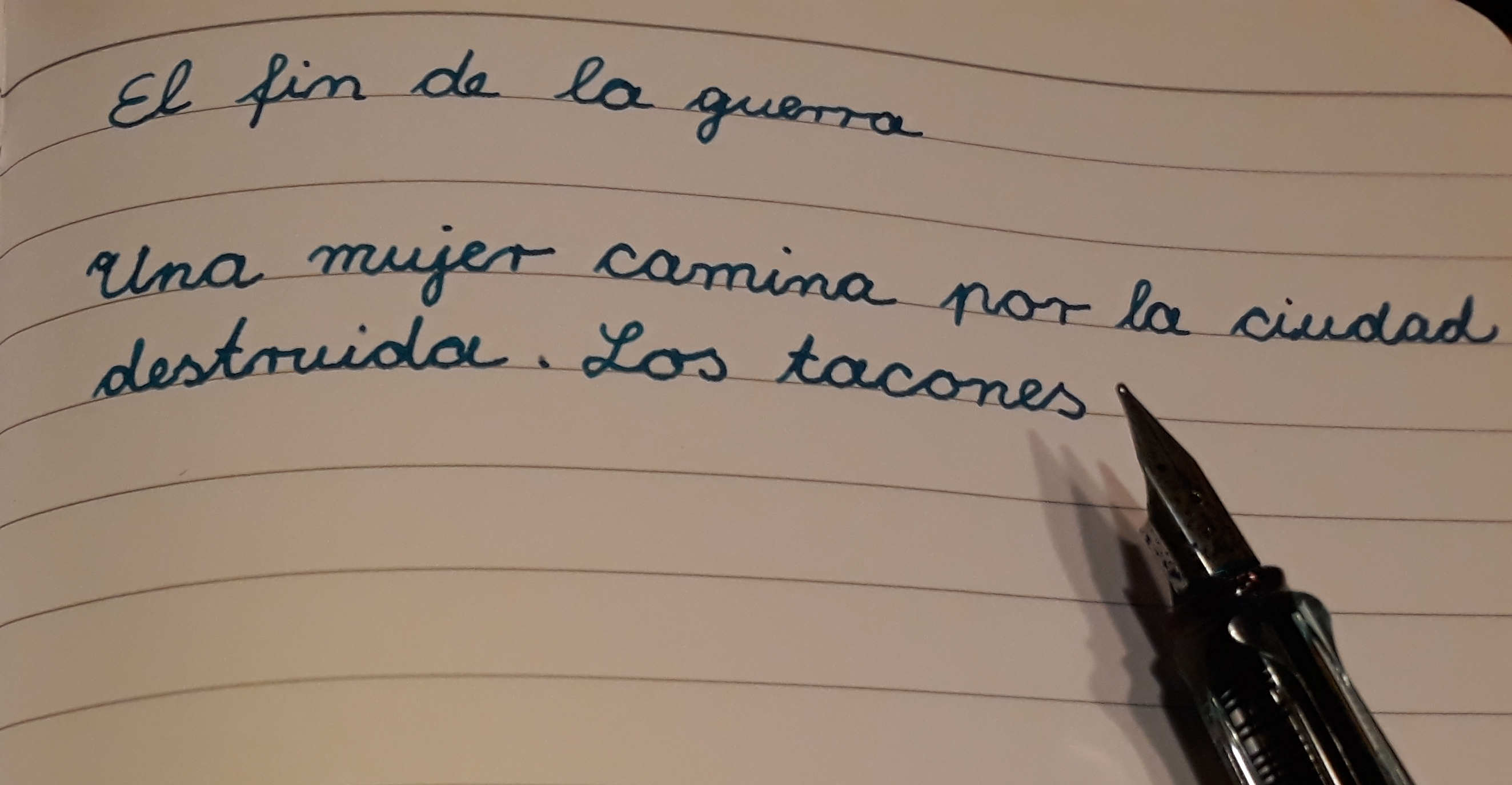

Una mujer camina por la ciudad destruida. Los tacones de sus zapatos resuenan en la acera polvorienta. La mujer pasa por ruinas, ladrillos abandonados y pilas de ceniza. Todo es gris o negro. Pero no la mujer. Su vestido delicado emite un aura festiva, los cabellos rubios están bien arreglados y sus ojos resplandecen de alegría. Ella sabe que la guerra ha terminado.

Una mujer camina por la ciudad destruida. Los tacones de sus zapatos resuenan en la acera polvorienta. La mujer pasa por ruinas, ladrillos abandonados y pilas de ceniza. Todo es gris o negro. Pero no la mujer. Su vestido delicado emite un aura festiva, los cabellos rubios están bien arreglados y sus ojos resplandecen de alegría. Ella sabe que la guerra ha terminado.